Article included in the Raise Your Voice zine curated by Baltan Laboratories.

When people dislike the direction an institution takes, they often call it ‘commodified’. In simple terms, commodification means putting a price tag on something that was previously free. Selling a gift, basically. But art & design education (hereafter simply ‘design education’) has always come with a price tag, being a gift only partially and only in specific circumstances, such as when accompanied by a scholarship. More commonly, this is not the case, thus education is a service that a student purchase, much like a good haircut.

The reason why I treat something as sacred as education in such mundane terms is that I believe the issue is not so much commodification itself, but the kind of commodity design education is becoming – specifically, a luxury experience. Just consider the tuition for non-European people studying in the Netherlands, which is growing at a ridiculous rate (sometimes increasing by 10, 15% from one year to the next), the housing crisis in many European cities (highlighted by the somewhat design-y protest in Barcelona with water guns shot at tourists), and, more prosaically, inflation. So, the increasing exclusivity of design education is both a systemic issue that can only be addressed at a governmental level, and one that is indeed shaped by the decisions taken by educational institutions alone.

What is to be done? Truth be told, educators like myself are in the worst position to influence institutions or even to demand transparency from them: we are temporary, disposable, fully alienated from any structural decision-making process. When it comes to facilities, infrastructure, organization of staff, student fees, etc., we remain in the dark, until the lights go on and it’s too late – the decision has already been made. In this sense, students seem to have more leverage, because they are not dependent on the school for subsistence.

That being said, in this article I don’t want to criticize luxury education, as its exclusivity is obvious. Instead, I want to praise a luxurious aspect of education which is positive and ought to be defended: leisure. If we think of luxury as abundance, then leisure is abundance of time. Design education can be – and perhaps already was – one of the few accessible place where “Fully Automated Luxury Communism” is actually possible. In fact, leisure is not something that education should aim to achieve, but what education fundamentally is: the word ‘school’ comes from the Greek skholē and the Latin otium, both meaning ‘leisure’. However, as we will see, it is precisely a malicious form of automation, or better yet, mechanization, that prevents this luxury.

Certainly, I’m not the first to champion leisure. To name a few, Bertrand Russell (In Praise of Idleness) and Josef Pieper (Leisure: The Basis of Culture) have made similar arguments. The former wrote: “At present, the universities are supposed to provide, in a more systematic way, what the leisure class provided accidentally and as a by-product”. The latter: “In leisure – not of course exclusively in leisure, but always in leisure – the truly human values are saved and preserved because leisure is the means whereby the sphere of the ‘specifically human’ can, over and again, left behind”.

Perhaps where my perspective differs from those above is in the use of the term. When I speak about leisure, I refer to something quite specific, at the same time similar to and different from the usual meaning of the word, that is, time free from work. I think of leisure not in terms of the content a school provides (such as fun, entertaining topics) but as the nature of the time spent within its walls. In this sense, leisure is about the rhythm of education. While education, not being work, seems leisurely by default (and yet what one does at school is not devoid of effort), its rhythm might make it worryingly work-like.

Leisure is the luxury of spending hours, if not days, on an issue or question whose utility and aim are not fully clarified, being those aim and utility part of the reflection. We shouldn’t confuse political urgency, that is, the present reality knocking at the school’s door, with an attitude that deprives us of the only wealth we have, both as students and teachers: time. Exactly because the things we care about are urgent, we need all the time in the world to address them.

Now, everything in contemporary education seems to conspire against a leisurely use of the educator’s time: nonsensical bureaucratic tasks, an increase in student numbers not matched by an increase in staff or teaching hours, new digital platforms that need to be learned, the management of hybrid teaching, and so on. The pandemic exacerbated all of this, to the point that several of my colleagues called it quits.

Many of these issues are both structural, if not global, since they’re determined by larger forces (think of the sudden hegemony of Microsoft Teams), and local, meaning that single institutions have a role to play. What about educators, then? Is there any role they can play? I tend to dismiss the idea that they are just passive victims of larger systems. Unfortunately, this non-passive view implies that not only are educators capable of improving those systems, but they can also contribute to their deterioration.

Such deterioration is sometimes due to what I call scapegoat syndrome. Educator suffers from this when they are willing to sacrifice themselves for a greater good, generally vague and abstract, such as the “the students’ well-being”. Teaching is traditionally considered a vocational activity, thus neither a job nor a profession. Now, a vocation needs to be displayed to others and to oneself. Self-sacrifice is a way to do so.

A clear example of scapegoat syndrome is when teachers stays at school overtime (one, two hours) to conduct tutorials with each student of classes of forty or even fifty. After a while, educators become exhausted by these extras and start shrinking contact time with students to fifteen, ten, even five minutes each. How far can one go? Ask Eubuilides of Mileto, who wondered: “if a heap is reduced by a single grain at a time, the question is: at what exact point does it cease to be considered a heap?”

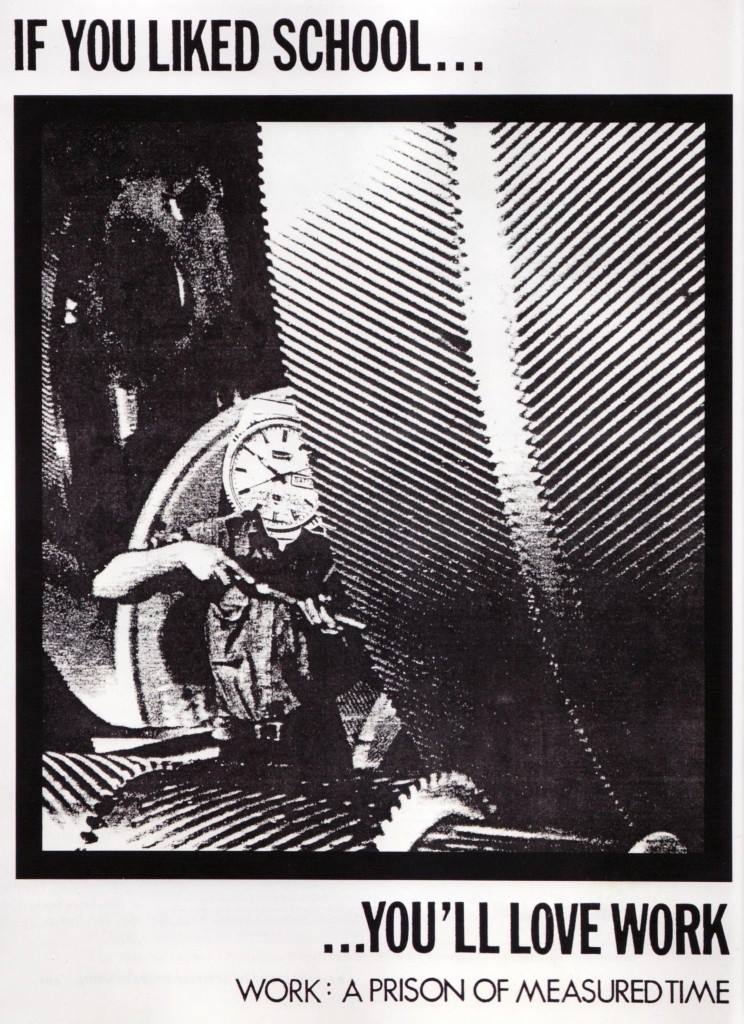

To manage such little heaps of time, you need to be efficient, and to be efficient, you need tools, which unsurprisingly are the same tools of the Taylorist factory – you need a stopwatch. During one of my first teaching experiences, after realizing that overtime was the norm rather than the exception, I uploaded an old poster in the school group. The poster depicted a worker with a wristwatch for a head, accompanied by these words: “If you liked school… you’ll love work. Work: a prison of measured time.” This is more or less what I wrote under the image: “To avoid delays, it was suggested to use a timer and be strict with the allocated time. I reject this form of rationalization. I’d rather risk speaking less with some of you than creating a Fordist tutoring environment that affects all of you.”

Some decades ago philosopher of design Vilém Flusser imagined a new kind of school in which technics would not looked down upon, “the place where homo faber becomes homo sapiens sapiens because he has realized that manufacturing means the same thing as learning”. In fact, he believed that this new model was already emerging: “Such factory-schools and school-factories are coming into existence everywhere.” His prophecy came undeniably true but, alas, in the worst possible way: most schools can be called “school-factories” not for the ennobling of craft and technology, but for the application of industrial modes of control and coercion. In my case, the content of education is still ‘educational’, but we begin getting alarmingly close to the school programs documented by Allan Sekula in his School is a Factory project, where education becomes a theatrical guise for semi-skilled job training of working-class students.

To challenge this industrial mode of education, or at least be alarmed by it, I propose the following rule of thumb: If a timer is needed during teaching hours, something is wrong at your school. Of course, final presentations are an exception (though a bit more time for toilet breaks would be appreciated).

The realization that something is wrong is good but insufficient. A further step is required: you, as a teacher, must refuse both to stay overtime and to taylorize your teaching. Hopefully, you’re not alone in this refusal. As a consequence, some students may be penalized because they have no chance to talk to you. So, they will complain. The crucial point is directing such complaint. If you help channel the complaint towards HR or management, suddenly the problem appears as structural, and it becomes clear that has nothing to do with you and your vocation. You don’t need to be the scapegoat anymore.

In addition to the rule of thumb, I want to suggest a threshold below which a school cannot be considered leisurely. This threshold shouldn’t not to be taken literally but rather as a guiding measure. This threshold is: thirty minutes of contact with a student minimum. If less time is available, we are in school-factory territory. What if only twenty minutes are needed? Then, something else will come up, perhaps more important than the tutorial itself. The student might finally find the courage to ask a question she was shy about, might seek an opinion on a sensitive issue, might open up about some crippling doubt of hers. The surplus time (‘surplus’ being itself an abuse of language) offered by the threshold is meant for the embarrassing silence, like the one that precedes the first question after a public lecture. That embarrassing silence is crucial for achieving a sense of comfort that allows us to address the things that really matter. As such, it must be protected and nourished. That silence is becoming a luxury, and that’s what’s truly embarrassing.