Afterword of Conspiratorial Design: Information Design for the Bigger Picture by Carlo Bramanti, published by Set Margins’ in 2025.

“But can one tell if All is a regular crystal, rather than more probably a monster?” – Alfred Jarry, 1911

“Information obeys no border. Once deep inside of any single thing you begin to find connections to everything.” – Don Koberg & Jim Bagnall, 1973

Our world is complex, right? So, how can one speak against something that just is? To answer this question, let’s consider a very tangible image of complexity (specifically, disorganized complexity), offered by Warren Weaver, a pioneer of communication theory: “a large billiard table with millions of balls rolling over its surface, colliding with one another and with the side rails.” This is the level of multiplicity we usually take into account when we speak about complexity (as real-life examples, Weaver mentions a large telephone exchange network and a life insurance company).

Now, I find the image of the billiard table beautiful and straightforward, but also pretty much unusable, unless you are a physicist, a mathematician—or the best pool player in the universe. Very few people work at that level of intricacy, and surely not most designers. Hence, my skepticism toward the idea of complexity as it is currently deployed within design, where every conference, syllabus or project description seems to be about ‘complex systems’.

I only became interested in this concept when I started noticing that, not complexity, but the very talk of complexity was becoming, in the design field, a cultural practice in its own right. As Guy Julier puts it, “it has become an orthodoxy to talk of the growing complexity of design in our ‘complex world’”. As with all orthodoxies, one stops questioning the dogmas that sustain them, allowing the primary goal of design—understanding a phenomenon before acting upon it—to be overshadowed by the discipline’s own conformism.

Keeping in mind the billiard analogy, one might also argue that the figure best equipped to handle complexity is not the designer, but the writer. This is because the writer finds themselves managing a de facto complex material, since their arena is the book, an object that appears to be linear and organized only when things are done and only superficially. In truth, the book (like the one you’re reading) is a complex object because each word interacts—and does so in multiple ways—with all the others, like and more than Weaver’s ivory balls in the pool table.

Furthermore, the idea that the complexity is growing in our society is actually untenable. In a viral (as well as bacterial) article entitled “Design Thinking is Kind of Like Syphilis”, Lee Vinsel asks: “What does this claim even mean? Complex in what way? Increasingly complex with respect to what metric? I have asked many professional historians this question, and they believe this increasing complexity claim is unsupportable.” Perhaps Theodor Adorno would have agreed, as he once stated that “society, wrongly scolded for its complexity, has in fact become too transparent”.

Some time ago, it became evident that many men think about the Roman Empire a lot, like every single day. Personally, I don’t, but I will make an exception and mention a couple of interesting theories about its fall to show that the world has always been shaped by distant, “nonlinear” and obscurely related factors. According to one of these theories, the fall wasn’t only due to short-sighted politics or war, but also, significantly, to the lead present in the cups that the members of the Roman elite used to drink, a substance that slowly poisoned them. Marshall McLuhan, on the other hand, building upon the work of Harold Innis, emphasized another factor, namely, a shortage of papyrus, which prevented effective communication on such a vast territory. This is all just to say that a certain degree of interconnectedness is not a unique feature of our present world.

If complexity (in a broad sense) is not a new phenomenon, and complexity (in a narrow sense) is practically useless to us, why is it so present in conversations and articles? The frequency of its use must fulfill another function. To identify it we need to think of how disciplines, and in particular the design discipline, work. Disciplines are arbitrary compartments of knowledge: they strategically define their boundaries in order to isolate some particular problems and solve them, or at least address them. Sociology, for example, was born in the early 19th century to address the problem (and, therefore, problems) of society. However, disciplines won’t meekly confine themselves within their artificial boundary; rather, their internal discourse will push the border, extending it. This tendency is especially evident in the design field, where you often hear that “everything is design”. Besides the physiological swelling of the disciplines, we witness a phenomenon which is historically specific. Martin Oppenheimer called it a “proletarianization of the professions”: when everyone can call themselves a professional, the reputational and financial returns of being one shrink. Furthermore, today there is a tangible distrust toward the figure of the expert. Just think of the field of economy or virology…

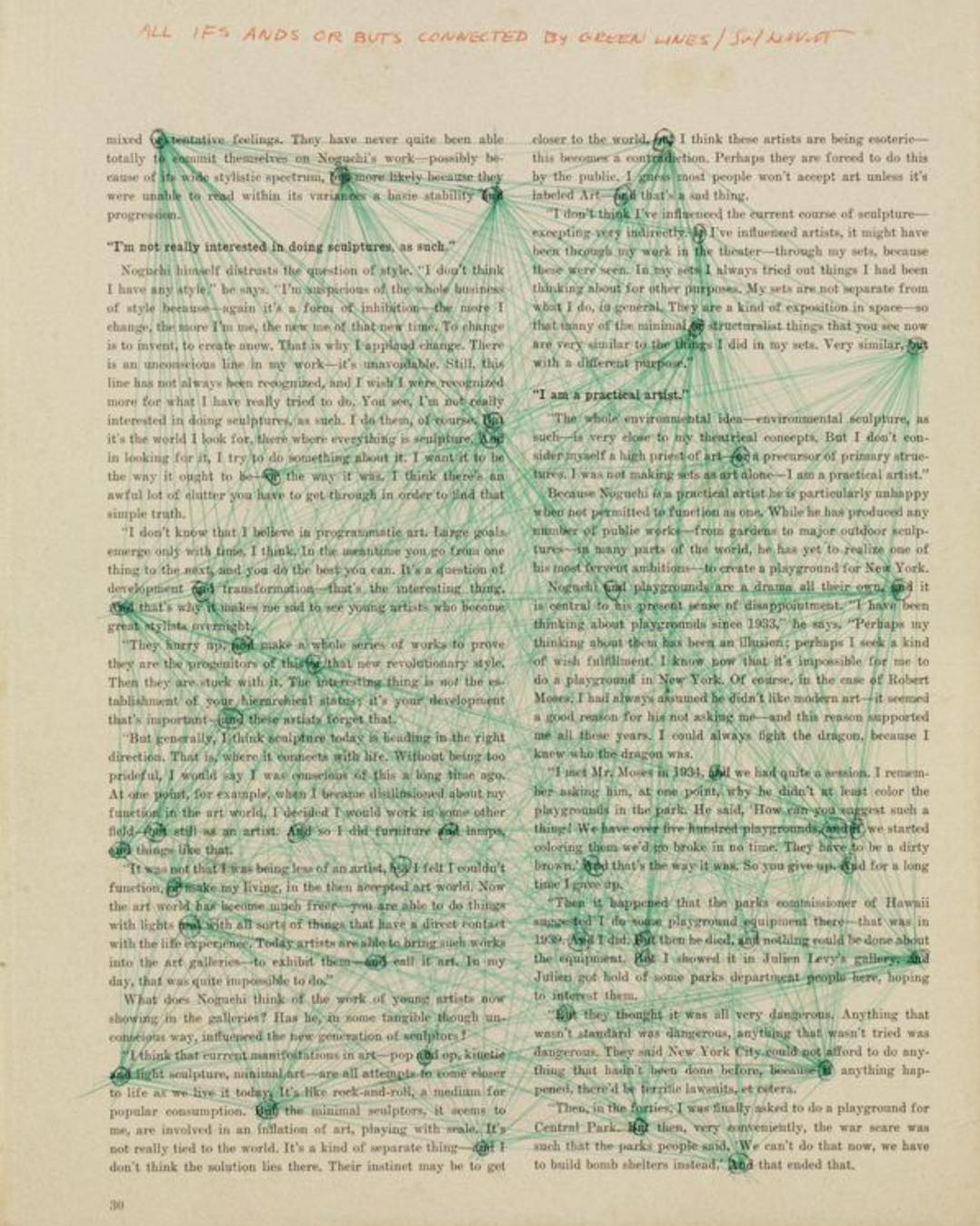

So, what do professionals do to regain prestige? They accelerate the expansion of the disciplinary confines, creating connections in an almost conspiratorial, apophenic mode. This book lucidly captures this process. With his notion of “conspiratorial design”, Carlo Bramanti shows that there are striking similarities, not only visual but also conceptual, between diagrams by legitimate design figures like Victor Papanek and paranoid-style infographics about “Covid 5G” by an obscure graphic artist named Dylan Louis Monroe. What do these artifacts have in common? They want to produce and project a sense of control on the messiness of the world. After all, as Richard Hofstadter pointed out, “the paranoid mentality is far more coherent than the real world, since it leaves no room for mistakes, failures, or ambiguities”. This could also be seen as an excess of the generalizing freedom granted by what Gregory Bateson called “the mysticism of symmetry and pattern”. How does the conspiratorial designer project a sense of control? By means of hypertrophy: by adding always more relations to their system, which becomes a totalizing one—it becomes the system.

This is why complexity is ultimately a reassuring category. Reassuring to whom? To the professionals, who are there to explain and clarify it, to seal it with “the authoritative stain of scientific enquiry”, as Georgina Voss puts it. And there is a further paradox. Do you remember the One Does Not Simply meme derived from Game of Thrones? Well, to reassure themselves, experts will have an incentive to expand their system of reference, and therefore to create more links and relationships. This leads to increasingly big and intricate diagrams, “the airport-bookshop model of systems thinking which tends to involve a lot of graphs and urges to ‘shift your mindset’”, as Voss again aptly describes it. But by adding links and relationships one does not simply reach “galaxy brain” level. Instead, their insights “can feel like a stoner monologue with pointed hand gestures”. Thus, they will likely generate more confusion, more noise, more chaos.

Chaos is a mysterious concept, but also one that doesn’t require any specific expertise—everyone knows what a chaotic room looks like. Chaos is the professional-disciplinary repressed that returns to haunt the expert of complexity. We hardly find the word ‘chaos’ in design articles and papers, because chaos is truly scary: it resists organization, it escapes any idea of controllable totality, it leaves us with undecipherable fragments. Whereas complexity reassures us, chaos forces us to confront our own powerlessness.

Shall we then just surrender to it? Not necessarily. As we have seen, complexity as a cultural practice is about totality: the world is complex, society is complex, etc. However, philosopher Cornelius Castoriadis indicates that the idea of a totality that can be encompassed by the intellect is nothing but a phantom of speculative philosophy. What’s more: we do not actually need it in order to exist in the world. Praxis, our acting in the world, is not a plan (closed and exact) but a project (open but not aimless): “every movement is a movement toward”. And yet, there is something real and concrete about totality. Who, among us, has never felt like the whole world is working against them? This is why, the material upon which praxis acts “does not give itself as totality, [but] it is as totality that evades us.”

Praxis is an ongoing negotiation between a general programmatic vision and a partial set of interventions on an “open, self-making unity”. While keeping track of its general ‘mission’, praxis recognizes that it belongs to a given space and time. Seeing its own specific point of view as a feature instead of a bug brings it close to what feminist scholarship calls “situated epistemology”. Ultimately, praxis means that we exist within the billiard table, and not outside of it. And as ivory balls must we roll, hoping not to end up in a pocket too soon.

— Silvio Lorusso, January 2025

This is a revised version of an intervention at Domus Academy’s roundtable, “Design for Complexity: Plural Perspectives on Systems Ambiguity”, featuring Allison Rowe, Georgina Voss, Matt Webb, and myself. The event took place on April 18, 2024.