Here’s an idea: operationally speaking, AI-generated images are disorienting because they disrupt the linear progression of refinement we’re accustomed to when it comes to traditional image-making production.

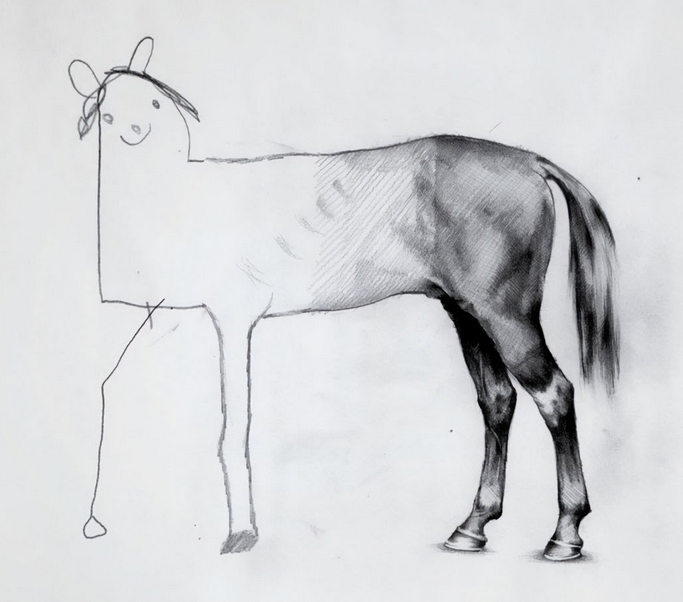

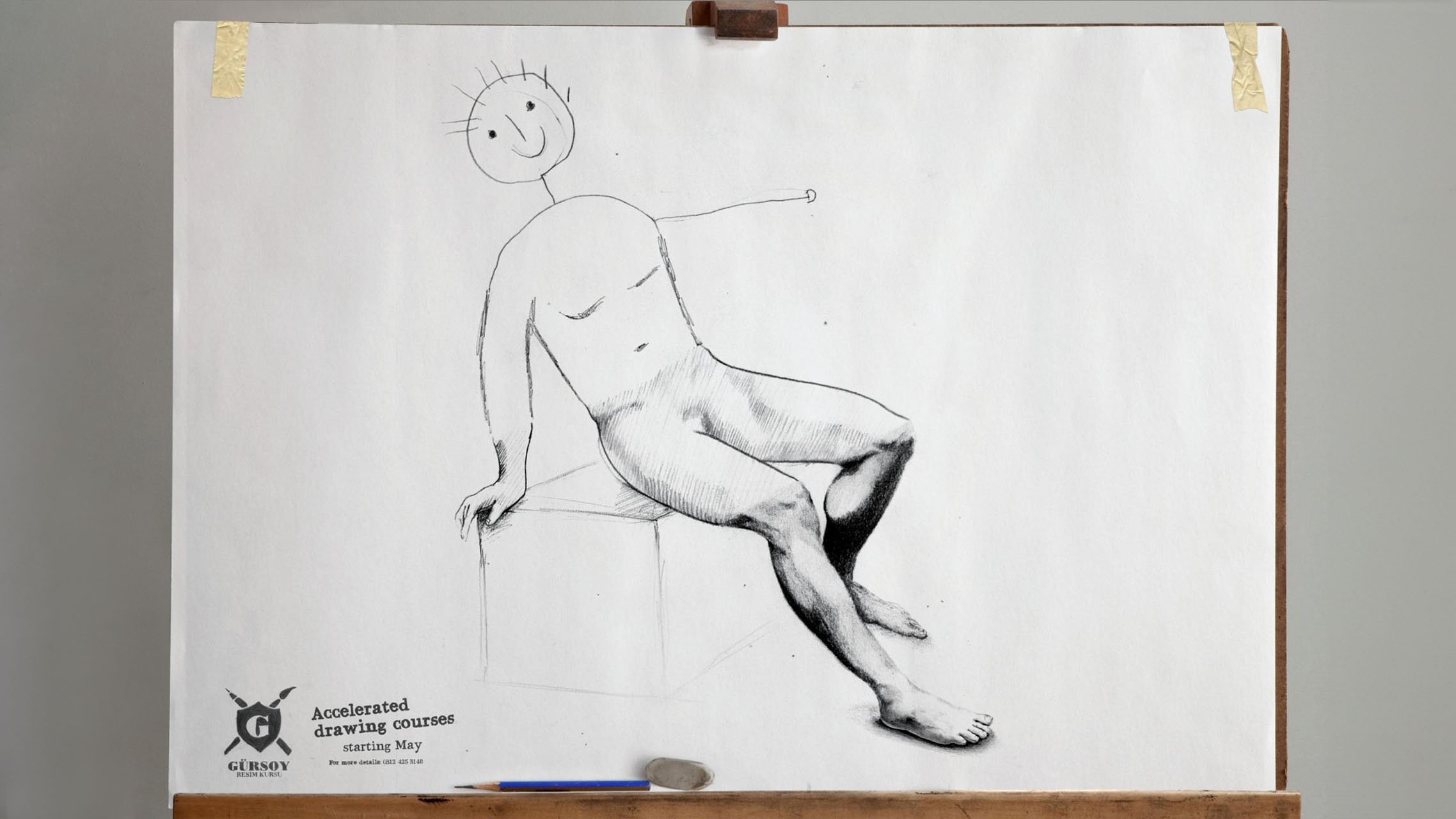

The progression I’m referring to goes from low to high resolution, from sketch to painting, from simplicity to complexity. We usually link a more detailed image to a greater amount of work. A realistic depiction of a cow generally takes more time to produce than a simple triangle with two straight lines for horns. A lo-res rendering requires more time than a high resolution one. Technically speaking, we tend to positively associate the effort put in a figure with its degree of “iconicity”, defined by Abraham Moles as the level of resemblance between a visual representation and the object represented. However, we need to keep in mind that this intuitive judgment is misleading, as a “simple” diagram may require as much effort to design as a detailed painting.

But doesn’t photography already break the effort/iconicity positive correlation? With the press of a button and minimal effort, we instantly get a photorealistic, highly “iconic” rendition of a real object. True, but we have to consider all the work that went into building the apparatus that makes the picture possible. Even so, we don’t find it strange that a such a realistic image is produced immediately, because we don’t see it as “constructed” (like a drawing or a painting), but rather as “captured,” stolen from reality, so to speak.

With synthetic images – where, at least for now, it often seems easier to generate a photorealistic cow than an accurate diagram of its anatomy – we encounter an operational incongruity: due to its photorealism, an image that should be understood as a sketch, mockup or rough prototype is instead intuitively perceived as a finished product.

I call this phenomenon sketchy realism, for two reasons. First, because the photorealistic image effectively functions as a sketch. Second, because the image itself is not to be trusted: it’s sketchy, in the deceptive sense of the word.

If, as Rob Horning suggests, the truth of an image lies in its use rather than in what it represents, it will take time to shift our mindset in order to see that truth. To do so we will have to detach images from the operational prejudices we’re used to (sketch: little effort, painting: a lot of work) This shift might even prompt us to rethink our categories when engaging with art, finally moving beyond criteria like obvious effort versus apparent effortlessness (“my kid could have done that!). In this sense, the sketchy realism of synthetic images might even help us better appreciate artists like Henri Rousseau, Jean Dubuffet, Asger Jorn.

Bonus: the unfinished artworks you haven’t seen, by Ali Bati, author of the horse.