Psychedelic dreams, oddly-fingered hands, plausible yet disturbing alternative realities – generative AI systems have finally unleashed the weird. But, in the process, haven’t they also normalized it? As a result, what we once considered weird is no longer so; instead, it has become a specific expression of classic kitsch. Let’s call it normie weird. If that’s the case, what happened to the real thing, what we could call weirdo weird, then? When one of the world’s leading tech companies releases a tool that produces crazy images reminiscent of a Max Ernst painting, something feels really strange. It’s not the images themselves, which we keep calling ‘surreal’ to bring them back to something known and therefore reassuring. Instead, what’s truly weird might be cloaked in derivative, pictorial, and ultimately visual aesthetics. The non-human core of a sprawling statistical entity could be lurking beneath a superficial layer of cute illustrations. This perspective confronts us with a haunting realization – that humanity itself is a kind of deep kitsch, and art, its greatest achievement, nothing but a shiny souvenir.

Transcript of a talk given at the Hidden Layers conference on the 14th of June, 2024. The conference took place at the Köln International School of Design and was organized by Prof. Dr. Lasse Scherffig, Matthias Grund, Jakob Kilian & Dzennifer Zachlod.

“Photography is bigger than us and is only minimally dependent on us. It is often capricious, sometimes even hates us. Occasionally, I get the impression that it pulls our leg. But this doesn’t really happen exactly to fools, who are always persuaded that they are the ones taking the pictures.” – Ando Gilardi1

A Dyson pollution mask, called Zone™, which gives you the desperate look of Batman’s antagonist Bane; a flamethrower (!) as the hobby project of one of the richest men on Earth; $55,492 raised to fund the making of a potato salad on Kickstarter. Also, more mundanely, the swarm of cubical bags toted day and night by food delivery riders throughout our cities. And all of this without even mentioning AI! When it comes to our technosocial environment, is there something that doesn’t feel weird nowadays? And yet, it seems that all this weirdness has anesthetized us, to the extent that if something makes total sense, we find it inauthentic and get suspicious. A touch of strangeness is what we expect, because weird has become so normal that its very absence feels weird.

What does weird mean, actually? According to Mark Fisher, the weird is that “which does not belong”, hence its most befitting aesthetic form is montage, “the conjoining of two or more things which do not belong together”. Fisher goes on to point out the penchant of Surrealism for the weird, and therefore the proclivity of its practitioners for unexpected juxtapositions.2 Our time feels, in fact, like a sequence of weird associations: Dyson vacuums plus Covid-19 equal Zone™, etc. Hence, the form of the montage, with its surreal twists, has itself become the default – something that belongs even too much.

Speaking of unexpected juxtapositions, artificial intelligence immediately comes to mind. When did AI begin getting weird? Generally speaking, one could say: since 1950, when Turing designed his famous test involving a computer programmed to imitate human intelligent behavior. Freaky, isn’t it? However, a more specific answer would be 2015, when Google launched Deepdream, a psychedelic computer vision program with no actual function whatsoever. Deepdream would generate images frighteningly similar to the surrealist paintings of Max Ernst. At that time, The Guardian asked: “Can Google’s Deep Dream become an art machine?”3 It became so for a little while, and then it did not.

Normie Weird

Adding to Fisher’s characterization of the weird, I’d like to argue that one could distinguish two kinds, relative, at least in part, to the viewer’s awareness: the level of normie weird and that of weirdo weird. The images generated by Deepdream are weird, sure, but normie-weird: they are what you would expect a weird image to look like. Somehow, they reassure us of our notion of weirdness. What feels (or at least felt) truly weird had to do with the very release of the software by Google. Deepdream wasn’t any niche artist software, but a research project hosted by one of the world’s largest corporations. As a comparison, imagine Ford launching a car named “Model Z” in 1930, featuring a built-in phonograph and vibrant polka-dot paint job. Of course, the launch of such a tool came with bold historical claims, aiming to secure its place in history. So, Blaise Agüera y Arcas, principal scientist at Google, compared Deepdream to photographic devices and instruments used by Renaissance artists: “tools which may have had their detractors, yet are now an accepted part of art history”.4

When everything is weird, nothing truly is. Dutch artist Constant Dullaart dedicated one of his latest shows to “sunsetting inconsistencies”.5 While most people interested in AI are future-oriented, Dullaart gives in to nostalgia: “The novelty of synthesized images has worn, and the naivety through which we grasp insight into opaque systems is a spell soon to strike midnight. On the brink but not quite, we find ourselves at an appropriate moment to salute that which is gawky and graceless to our human eyes.”

One of the artworks in the show is a hyper-realistic silicone sculpture of an oddly-fingered handshake. With this artwork, entitled Accepting the Job (a nod to the debate about robots replacing humans in the workforce), Dullaart pays tribute to the most popular type of AI incongruity. This work exemplifies the belief that, since AI systems are quickly improving, weird phenomena will become rare and, ultimately, extinct. In my opinion, something else is happening: some inconsistencies (both old and new) are here to stay, but we will get use to them, as we got used to the haunting static noise of TV or the wretched collages of panoramic photos taken with a smartphone. Therefore, what Dullaart’s sculpture anticipates is not so much the sunsetting of the weird, but its conversion into kitsch. In fact, the handshake is an aloof object that doesn’t perturb us – it’s normie weird. This, however, doesn’t mean that Dullaart’s work is kitsch. Quite the opposite: it’s a confirmation, on a deeper level, of his sentiment towards AI. Thanks to Dullaart, where everybody sees ‘the future’, we already see the past – we see the lie.

Classic Kitsch

Everybody intuitively knows what kitsch is about. Yet, there are endless interpretation of this concept. According to Domenico Quaranta, “[g]oing through the vast literature about kitsch, it’s hard to resist the feeling that our contemporary notion of kitsch is not the result of any kind of evolution or progress, but rather the overlapping and coexistence of different ideas. […] All of them, to some extent, still hold true today, and taken together they all shape our contemporary, contradictory, layered, vague yet clear idea of kitsch.”6 Here, we cannot be satisfied with this vague yet clear idea, but we need to make distinctions. In parallel with the normie weird / weirdo weird pair, we can formulate one involving classic kitsch and deep kitsch.

Classic kitsch is the souvenir of Michelangelo’s David. In 1976, Umberto Eco explained that the word “kitsch” comes from the English “sketch” and refers to the copies of masterpieces that well-to-do gentlemen would purchase during their Grand Tour. Eco defines kitsch as “art’s lie”, namely, all that is not the real thing. Among the examples he gives, drawing from Gillo Dorfles’s classic study on the subject,7 are the Mona Lisas reproduced on an apron, a glasses case and the packaging of a cheese.8

Postcard of Leonardo and Mona Lisa at the Movieland Wax Museum in Los Angeles, shown by Umberto Eco.

The lie can be less than the original (a David made of plastic rather than Carrara marble), or more: Eco, for instance, mentions the Movieland Wax Museum in Los Angeles where one could witness the scene in which Leonardo is portraying the Mona Lisa. In such context, visitors can see not only her torso, but all of the body – “they have more of the Gioconda”. Here we find an analogy with AI, as the so-called outpainting feature was used extensively to expand album covers (as well as – ça va sans dire – Leonardo’s masterpiece).

‘More’ can also be understood in terms of quantity, and therefore reproduction. By default, Midjourney generates four versions from a prompt, arranged in a grid reminiscent of Warhol’s series of Monroes. Thus, with AI we have reproduction without original, more without one, a lie that doesn’t refer to any truth.

Finally, ‘more’ can refer to the amount of details. A classic example of kitsch is the little gondoletta veneziana, with all its intricate rococo decorations. Maximalism is also what drives the “make it more” trend, in which users push AI image generation to the limit by asking ChatGPT to imagine, say, a spicy ramen and then ask for a spicier one ad infinitum, until cosmic spiciness is reached.9 I suspect that this trend embodies the production of synthetic images in toto: always more intricate, more dreamlike, more absurd, more improbable, more weird. And again: more realistic, more virtuosic, more hi-res, more picturesque, more vintage, more macro, more micro.

Deep Kitsch

I can’t resist making a final (and admittedly obvious) parallel between classic kitsch and AI: a photograph of the pope in a frame adorned with seashells – the pope in question being not the Moncler-aficionado Francis, but John XXIII. The owner of such an artifact is a lawyer called Polli, collector of kitsch, interviewed four years before Eco.10 Polli uses highfalutin expressions to speak about his collection, such as “museum of horrors”. His attitude is one of ironic distance. But, what’s truly kitsch here? More than the objects, somewhat honest and innocuous, the lofty rhetoric of the lawyer, his display of good taste via bad taste, strikes us as mystifying. Polli is an instance of what Broch called the kitsch-man, “the lover of kitsch; as a producer of art he produces kitsch and as a consumer of art is prepared to acquire it and pay quite handsomely for it.”11 He’s the heir of the cultivated grand tourist, adamantly certain of his knowledge of art and history, who brings back some peculiar collectibles from the voyage to display his sophistication.

Nowadays, the journey takes place in our computers. While, until some years ago, we would surf the web to find gems hidden in some little-known corners of the internet, today we use Google Images. In fact, the activity which comes the closest to synthetic image generation is neither painting, nor photography, nor photo editing, but image search. The practices are similar: both involve entering a string of text and a few parameters. Moreover, one activity flows into the other: what is the generative act if not an immense, probabilistic image search? And viceversa: it is becoming difficult to do a search online without running into a good deal of synthetic junk. The image searcher is like the tourist who “discovers” a beach – only to find it full of the trash left by previous tourists.

What does the digital tourist appreciate? From Deepdream on, AI art appeared generally oneiric, surrealistic, psychedelic – weird in a ‘dreamy’ sense. Weirdness is in fact the chimera of those who make art with text-to-image systems (TTI), and want it to be seen as such. AI artists try to persuade themselves and others that what they are doing is probing the limits of the medium, when in truth the medium (read: those who program and feed it) purposely pre-packages the weird. Unsurprisingly, -weird is a built-in Midjourney parameter, therefore an option, a style among others. The overall effect is measured in terms of intensity. Like with Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory, a painting that was originally very powerful, we start to feel a growing indifference towards its many variations, until what we experience is outright annoyance. TTI services lead to a similar outcome: they normalize the weird, and surround it with a deep-kitschy rhetoric of artistic refinement. This is why we can consider the AI artist as the latest iteration of Broch’s kitsch-man.

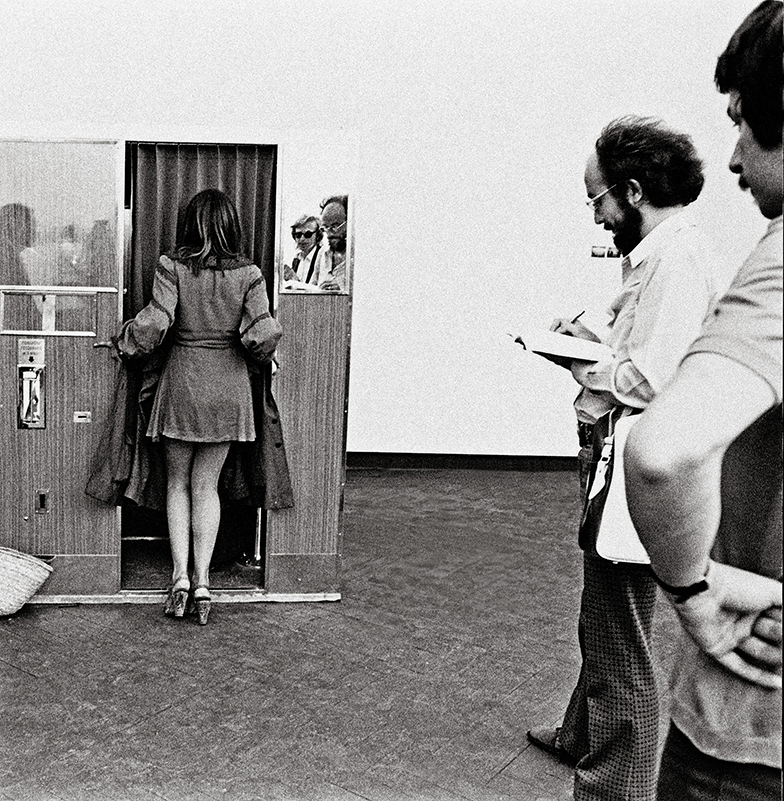

Franco Vaccari, Esposizione in tempo reale n°4, Lascia su queste pareti una traccia fotografica del tuo passaggio, 1972.

Franco Vaccari, an artist who in 1972 placed an automatic photo booth at the Venice Biennial, identified a similar kind of deep kitsch in the field of artistic photography. Historian Roberta Valtorta explains his point of view: “Vaccari senses the enormous potential of the camera when it is not used and guided in a forcefully ‘artistic’, deliberately ‘creative’ (ultimately pictorial) manner, but it is given the freedom to operate as an instrument capable of producing records and memories independent of the operator’s intentions and abilities. This makes it a powerful tool for checkmating (I use this term thinking of Duchamp) rules, visual and behavioral habits, both private and collective, whether derived from individual histories or the conditioning induced by media and power”.12

Vaccari’s polemical target was the photographer’s intentionality, which was generally expressed pictorially. He had in mind photographers like Cartier-Bresson, as they would insist on the soothing poetic of the instant décisif, a moment which could only be captured by a particularly sensitive subject. Vaccari writes: “Photographers, structuring the image according to their own aesthetic beliefs and experiencing them as objective, lose themselves in a tautological situation where they encounter nothing but their own projections; the imaginary is experienced as real and photography becomes the place of mirages and ghosts.” In other words, photographers would “supercodify” the image with their values.13

What is the ‘code’ in question? The vulgar code of the “social climbers, who embrace the ‘jargon’ of the classes to which they aspire”, just like Polli who emulates the elite’s good taste through irony – but instead just displays an insufferable elitism. Vaccari speaks of scabbing, of “class betrayal”.14 The same happens now in the context of AI, where both users and software engineers charge their tools and their generated images with an “an atmosphere of artistic theory, a knowledge of the history of art: an artworld”.15 This artworld is surreal, oneiric and dreamy, because dreamy, oneiric and surreal is what we expect it to be.

AI imagery, like kitsch, “sells itself as art without reservation”,16 and, like art, tries to obtain its place in history. In this sense, AI art is doubly retrospective. First, in a technical sense, in that synthetic images derive from a pre-existing dataset. To some extent this is true for any image, however, datasets are characterized by a precise threshold: the collection, for example, might have ended in 2021. Second, these images are retrospective in a cultural sense: looking at them, one has the feeling that today’s visual trend will be obsolete tomorrow. Hence, all the attempts to connect, serialize, comment, catalog, musealize them… that is, justify such images. Through a do-it-yourself canonization one tries to save them from the impending abyss.

Weirdo Weird

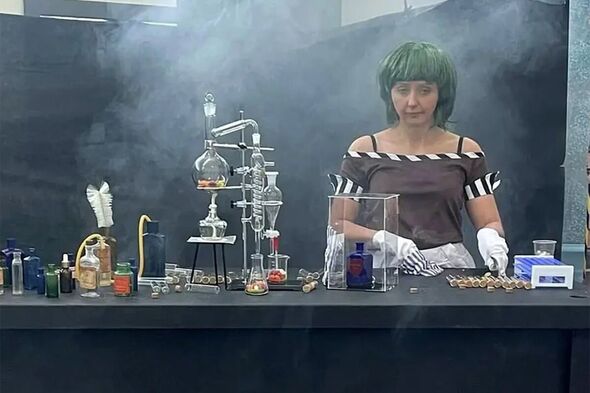

To find an instance of weirdo weird, we need to look outside the AI image. Here’s the story of a scam: some TTI-generated illustrations advertise a spectacular, immersive experience inspired by Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory. But the attractions are cobbled together, to say the least, and sporadically placed in an otherwise grungy warehouse. The overall feeling: deep sadness. Disappointed visitors consider themselves defrauded and demand a refund of the pricey ticket.17

Whereas the AI-powered advertising is as boring as stock photography, the images documenting the experience (and arguably the experience itself) are worth the price of the ticket: truly ‘liminal’, strangely memorable, they wouldn’t be out of place as the background of a weirdcore picture.18 Such is the spectacle. With a minimal expenditure of means, ‘reality’ succeeds in producing what the scouts of “the latent space” promise and fail to deliver: weirdo weird. According to a Twitter user, one of the photos, that of a depressed actor dressed like an Oompa Loompa, should be nominated photo of the year. While the synthetic strangeness is not strange enough, here we get a clear sense of what “doesn’t belong”. It’s not just these cheap plastic sculptures that have no place in a shabby warehouse, but we ourselves: “what am I doing here?”, asks the perplexed visitor. Of course, the process of normalization of the weird has already begun: there are people who want to recreate the experience, in an event starring the somber Oompa Loompa.19

Domenico Quaranta advances a bold thesis, namely, that digital production is inherently kitsch: “digital kitsch is understood as the default mode for creative endeavors that use digital media: tools that have made visual literacy accessible to all and rendered the strategies and languages of the avant-garde banal and commonplace; tools that elicit technophilia, rather than critical, informed use, and are characterized by built-in limitations and ideologies that condition their creative outputs.”20

The mode described by Quaranta has been anticipated by those artists who made use of avantgarde strategies, such as collage, before their banalization.21 William Burroughs, for example, who developed the cut-up technique, saw language itself as a virus. This idea turns human beings into passive vessels of an alien entity that travels autonomously through them. All that makes us human, all our aesthetic and moral values, our taste… they don’t matter anymore. All that is Art, ‘humanity’s greatest achievement’, suddenly appears tacky. But this feeling only hides a more daunting realization: that humanity itself is kitsch like a dingy souvenir, that human beings are outdated, as Günther Anders pointed out in 1956. Anders spoke of “Promethean shame”: confronted with the complex machines that humans invented, the individual cannot help but feel deficient.22 These machines looks weird because we don’t understand them, so the shame we feel is not about them, but about us. Mark Fisher explains why: “The weird thing is not wrong, after all: it is our conceptions that must be inadequate.”23 When everything feels like it doesn’t belong, it’s because it is us that actually don’t. The kitsch-man gives way to the man as kitsch.

If there is no human value that doesn’t feel oleographic and quaint, to escape deep kitsch we have to look at “the increasing inhumanity of the intelligence we’re developing”.24 There, we might find what Lev Manovich calls “another systematicity” and optimistically believes we will fall in love with.25 Is there any artwork capable of bringing such non-humanity to the fore? There are plenty of xeno works, but they often fall in the trap of normie weird: they reassure us presenting the alien how we expect it to look like.

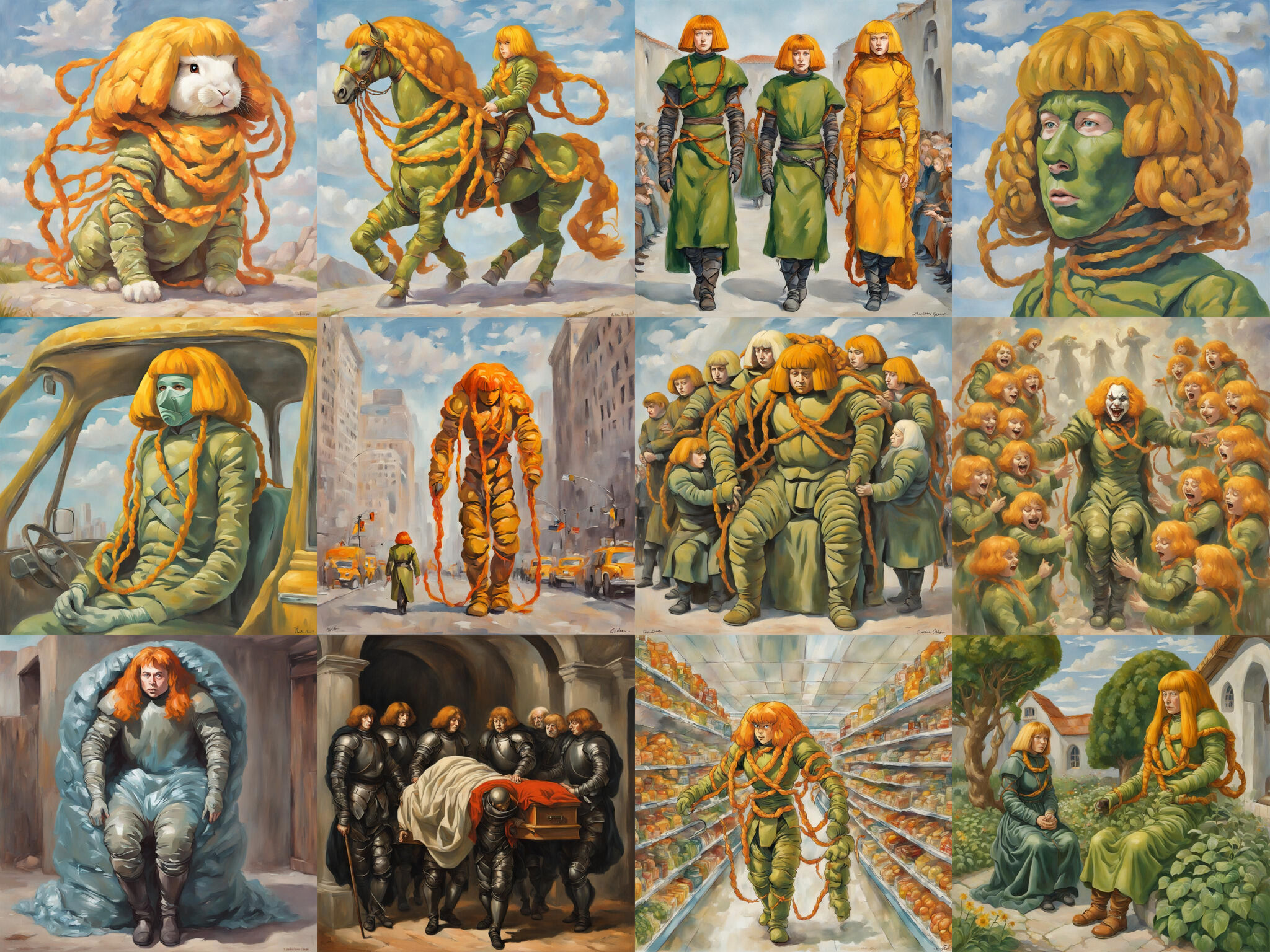

What if the alien is cloaked in classic kitsch, instead? Take Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst’s xhairymutantx. At first glance, what we see are cutesy, painterly, sometimes Studio Ghibli-ish illustrations of the ginger-haired musician. But what’s happening here is way more haunting. As the artists put it, “’Holly Herndon’ is not just a person. The name also designates a distinctive internet presence: a female character with white skin, red hair, blunt-cut side bangs, and bright blue eyes.”26 This is an inhuman description of Holly, based on features that acquire a mathematical value within text-to-image AI programs. The artists selected the most recognizable one, the singer’s hair, and exaggerated it, treating her appearance as some sort of abstract, tokenized Frankenstein’s monster.

We look at the kitschy, all-too-human Holly illustrations and we get a glimpse of the deeply weird, other-than-human ratio of the system. We sense – more we cannot do – the sprawling statistic entity behind the brushstrokes and that makes us feel slightly uncomfortable. We perceive the weirdo weird without fully understanding it. We try to cling to this haunting feeling provoked by the median and the average, because we know that if we let it go, we’ll fall once again into the comfort zone of normie weird, where shiny artifacts entertain us, like floating toys in a baby cradle.

1 Gilardi, Ando. 2021. La stupidità fotografica. Monza: Johan & Levi, p. 29. This and the following translations from Italian are by the author.

2 Fisher, Mark. 2016. The Weird and the Eerie. London: Repeater Books, pp. 10-1.

3 Rayner, Alex. 2016. “Can Google’s Deep Dream Become an Art Machine?” The Guardian, March 28, 2016, sec. Art and design. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/mar/28/google-deep-dream-art.

4 Ivi. As we generally ask what’s in the dataset, it is interesting to ask what’s in the model of engineers in terms of artistic references. In a TED Talk about Deepdream, Agüera y Arcas mentions the following artists and uses the following artistic qualifiers: Michelangelo, William Kentridge, Escher, surreal, psychedelic, cubist, “kinda crazy”. Agüera y Arcas, Blaise. 2016. “How Computers Are Learning to Be Creative.” TED. June 28, 2016. https://www.ted.com/talks/blaise_aguera_y_arcas_how_computers_are_learning_to_be_creative/.

6 Quaranta, Domenico. 2023. “Digital Kitsch: Art and Kitsch in the Informational Milieu”. In Max Ryynänen & Paco Barragán (eds.), The Changing Meaning of Kitsch: From Rejection to Acceptance. Palgrave / MacMillan (Springer Verlag). pp. 205-228.

7 Dorfles, Gillo. 1969. Kitsch. An Anthology of Bad Taste. London: Studio Vista.

8 Radiotelevisione svizzera (RSI). 2022. “Umberto Eco e il kitsch | Cliché | RSI.” YouTube. June 3, 2022 [October 12, 1976] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n3jS4Pmvtns.

9 See Antonio, Jose. 2023. “The ‘Make It More’ ChatGPT Trend—and How to Play along at Home.” Decrypt. November 29, 2023. https://decrypt.co/208002/make-it-more-chatgpt-trend-and-how-to-play-along-at-home.

10 Radiotelevisione svizzera (RSI). 2022. “Il Collezionista di kitsch (1972) | Sette Giorni | RSI ARCHIVI.” YouTube. December 27, 2022 [December 17, 1972]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cnNp__1a07E.

11 Broch, Hermann. 1969. “Notes on the Problem of Kitsch.” in Dorfles, op. cit.

12 Valtorta, Roberta in Vaccari, Franco. 2016. Fotografia e inconscio tecnologico. Torino: Einaudi, p. XII.

13 Vaccari, op. cit., pp. 13-4.

14 Ibid., p. 43.

15 Danto, Arthur. 1964. “The Artworld.” The Journal of Philosophy 61 (19): 571–84, p. 580.

16 Eco, Umberto. 1977 [1964]. Apocalittici e Integrati: Comunicazioni di massa e teorie della cultura di massa. Milano: Bompiani, p. 112. Translation by Domenico Quaranta.

17 See Brooks, Libby. 2024. “Glasgow Willy Wonka Experience Called a ‘Farce’ as Tickets Refunded.” The Guardian, February 27, 2024, sec. UK news. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2024/feb/27/glasgow-willy-wonka-experience-slammed-as-farce-as-tickets-refunded.

18 See Tanni, Valentina. 2024. Exit Reality: Vaporwave, Backrooms, Weirdcore, and Other Landscapes Beyond the Threshold. Rome, Ljubljana: Nero, Aksioma.

19 Davies, Caroline. 2024. “Glasgow Willy Wonka ‘Chocolate Experience’ to Be Recreated – in LA.” The Guardian, April 10, 2024, sec. UK news. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2024/apr/10/glasgow-willy-wonka-chocolate-experience-recreated-los-angeles.

20 Quaranta, Domenico, op. cit., p. 205.

21 For a tragic anticipation of the digital recombinant mode in the work of graphic designer Stefano Tamburini, see Lorusso, Silvio. 2024. “Synthetic Chav, Compulsive Synthesis”. Text accompanying the exhibition Stefano Tamburini, Accelerazione curated by Matteo Binci and Valerio Mattioli, MACRO Museum, Rome. https://silviolorusso.com/publication/synthetic-chav/.

22 Anders, Günther. 2014 [1954]. L’uomo è antiquato: Considerazioni sull’anima nell’epoca della seconda rivoluzione industriale. Torino: Bollati Boringhieri. Italian essayist and artist Francesco D’Isa also reads the development of AI through the lens of Anders’s Promethean shame, inviting us to let go of humanity (a value that Anders clings to) and make AI systems more inhuman, that is, less shaped by our desires and preconceptions. D’Isa, Francesco. 2024. La rivoluzione algoritmica delle immagini. Bologna: Luca Sossella, p. 146s.

23 Fisher, op. cit., p. 15.

24 Bridle, James. 2017. “Machine Learning in Practice.” Intersections: Art and Digital Creativity in the UK. April 24, 2017. https://medium.com/intersections-arts-and-digital-culture-in-the-uk/james-bridle-machine-learning-in-practice-d7cb58cd20cb.

25 Manovich, Lev. 2019. “Defining AI Arts: Three Proposals”, AI and Dialog of Cultures, exhibition catalog, Hermitage Museum, Saint-Petersburg. http://manovich.net/index.php/projects/defining-ai-arts-three-proposals.