Silvio Lorusso: Dear Jordan, thank you for accepting my invitation. You built a full-fledged open source HTML, CSS and Javascript emulator of Winamp, the most iconic pre-iTunes media player, which many of us remember for the possibility of customizing it with crazy, hand-coded “skins”.

As you told Techcrunch, it seems that these skins were the original inspiration for your project. What’s your relationship to this piece of software? Do you have any special anecdote about it? Elsewhere you stated that skin design was “the first constructive creative work you did on a computer.” Is this skin still accessible?

Jordan Eldredge: Winamp’s origin is culturally linked to the emergence of the file sharing program Napster. Overnight, anyone with a computer could access the largest library of music in history — for free. Not only did this let us download popular songs without having to pay, but suddenly we could access music that the music industry didn’t want us to have. From irreverent prank phone calls, to songs by bands too niche to be worth a record company’s time, Napster was how you acquired it and Winamp was how you listened.

Not only was this a watershed moment for technology and music, but it came during my generation’s teenage years, when musical tastes are often central to defining one’s own identity. With Winamp and Napster we were shown a world where software was a force that could invert the power dynamic between corporate America and consumers. Suddenly, young people saw software as means to own their own culture and assert themselves in the world. This software was punk rock.

Winamp and Napster were tools that gave you power. Winamp was the weapon we wielded in our youthful rebellion against those in charge. Naturally we would want to polish it and make it our own. Viewed in this light, it becomes obvious why the look of this software would be user-configurable.

It was in this context that I first got curious about how Winamp skins were made. While I was no artist, I was in awe of the effects artists on the internet were able to achieve. I remember spending many late nights pouring over forum posts trying to understand how skins were made — and how I could make one myself. I vividly remember the moment when I first saw pixels I had drawn — ugly though they were — rending as part of an application that I could interact with. All these years later, I think I’m still chasing that same thrill.

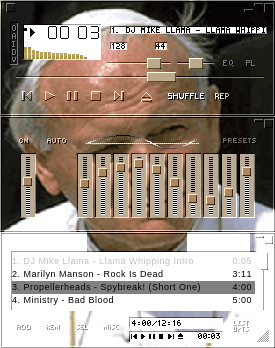

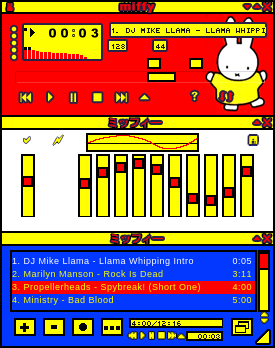

As part of the Webamp project, I partnered with the Internet Archive to preserve over 65 thousand Winamp skins. Among them is the one (ugly) Winamp skin I made all those years ago. You can find it in the skin archive

SL: I suspect recreating Winamp in a browser was not an easy task… How long did it take you to have a workable prototype? What were the most challenging functions to replicate?

JE: One evening in 2014 a memory of Winamp skins popped into my head, and it occurred to me that they were implemented using sprites, which I had recently been using on the web at work. Could I use the same techniques I was using at work to render a Winamp skin in the browser?

That evening I stayed up late and proved to myself that it was, in fact, possible. Over the next few weeks I managed to get a version working that could render the main window and play an mp3. I tweeted about it, and it received far more attention than I anticipated, including a writeup by Gizmodo.

Inspired by this interest, I’ve continued to tinker with the project in my spare time. By 2018 I had added a fully functional equalizer and playlist. When I shared this news, the project really took off, getting write ups from hundreds of news sites and blogs around the world.

I think the most difficult aspect of this project has been the sheer variety of challenges it has presented. Like a course catalog at a university, each feature offered an opportunity to learn a different aspect of software development. From audio signal processing and collision detection, to compiler construction and graph traversal, this project has provided an endless supply of interesting and enticing opportunities to teach myself computer science fundamentals. As a self-taught programmer, I feel like Webamp has been my equivalent of a university education.

SL: Wow, Jordan, it is fascinating to hear of all the technical complexities lurking “under the skin”. And I can fully relate to the sense of empowerment that Winamp, together with Napster, (as well as WinMX and Emule) provided at the time. In fact, it seems to me that empowerment can be seen as the thread connecting the past to the present: in the early 2000s, Winamp meant emancipation for a big cohort of online users, while more recently it worked for you personally as a form of self-education.

I must admit, though, that I get a bit melancholic when I think of that golden age. Now, in times of “netstalgia” and “techlash”, do you see any Winamp-equivalent? Namely, some software or platform or community as empowering as the good ol’ peer-to-peer ecosystem of yore?

JE: For me personally, the freedom and empowerment that peer-to-peer file sharing promised was ultimately delivered by the open source software movement, a model where people build software and then release the code for anyone to use, study, change or resell for free.

The way that this movement has evolved from the hobby of a few idealists into a core strategy of most of the worlds largest software companies has been extraordinary. The fact that much of the most important software in the world is free for anyone in the world to read, use and modify is unbelievably empowering.

I often daydream about ways the model of open source could be applied to crafts other than programming. For example, now that recorded music can be distributed at essentially zero cost, could passionate amateur musicians collaborate on musical recording which they release directly into the public domain?

One of my favorite music projects is the Open Goldberg Variations, which was a Kickstarter campaign which raised $23,000 to make an exquisite studio-quality recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations which was released into the public domain.

Having this recording in the public domain means that it can be used as source material for all kinds of non-commercial art projects. For example, there’s a whole ecosystem of people on Youtube using this recording to create beautiful computer visualizations which lay bare the intricate complexity of Bach’s composition.

SL: Speaking of public domain, can you tell me more of the partnership with the Internet Archive? Of course, I’m not surprised of their interest since they’ve been preserving the material culture of networked computers in the broadest possible sense…

JE: One of my goals with Webamp was to try to recreate the behavior of Winamp as accurately as possible. Even going as far as to reproduce some bugs. As part of that quest, I ended up seeking out skin files and noticed that the websites that had originally hosted them were starting to fall offline. It occurred to me that the Internet Archive might be able to help. I tweeted a question about it, and a friend put me in touch with Jason Scott.

I had the vision that not only could we preserve the files, but we could keep them accessible. We could use Webamp to programmatically generate screenshots, and on each skin’s page we could include an instance of Webamp with that skin loaded. I loved the idea any Winamp skin ever made could be fully experienced and shared with just a click.

When I shared this vision with the Internet Archive, they went one step further and also integrated Webamp as an optional audio player for their thousands of collections of audio files. You can read about it on their blog.

SL: It’s quite impressive to see the ecosystem emerging around Webamp. I see that on the skins’ archive, users are able to flag “not safe for work” ones, but I assume there are also offensive ones. Is this the case? Did you stumble upon any of them?

Yes! One piece I forgot to mention in our discussion of open source software is that Webamp is itself open source. As a result a number of projects have been able to use it as a building block. Some examples include Winampify which is a Spotify client which uses Webamp as the main user interface and 98.js.org and winxp.now.sh each of which recreate a classic version of Windows in the browser.

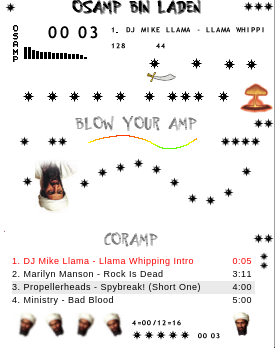

The issue of NSFW skins has been a quite interesting. It was humbling to confront just how subjective the notion of “safe for work” really is. A skin would strike me as clearly pornographic, and then the very next flagged skin would have nearly identical content, but the image was taken from the cover of a best selling album. In addition to pornography, as you point out, there are other types of offensive skins. For example, one that feature Nazi or Taliban icons.

The good news is that the Winamp Skin Museum is a mostly insignificant microcosm of these issues. I doubt anyone is going to become “radicalized” by a Winamp skin. There are certainly many distasteful skins, and while it might be nice to have a museum of only “nice” skins, I think it’s more valuable to preserve the ugly alongside the sublime and thus, in some way, preserve a more imperfect and human snapshot of this cultural moment.

SL: Winamp was shut down in 2014, did they contact you in any way?

JE: When I first announced the project, under the awkward name “winamp2-js”, one of Winamp’s original creators reached out and offered me the “Webamp” domain names. To me, this was like having your favorite rock band send you a signed guitar. I’m still humbled by that generosity.

Today, Winamp belongs to the company Radionomy. Those owners did at one point reach out to me with a request to meet up and talk. It was unclear exactly what they had in mind and due to some travel and timing issues, we were never able to make the meeting happen.